A Daughter Restores Her Stunning Childhood Home

When the house was built in 1959 by midcentury designer and builder Rodney Walker, its glass-walled, steel I-beam construction captivated the residents of Ojai. It was one of the few modern houses around. (Walker had gained recognition 12 years earlier for designing three of the famous Case Study Houses sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine.)

It was this specialness that eventually inspired Gray’s return and spawned a careful renovation, the home’s first. She fixed a leaky roof and updated the kitchen and bathrooms but otherwise sought to preserve Walker’s original design — along with her childhood memories — as much as possible.

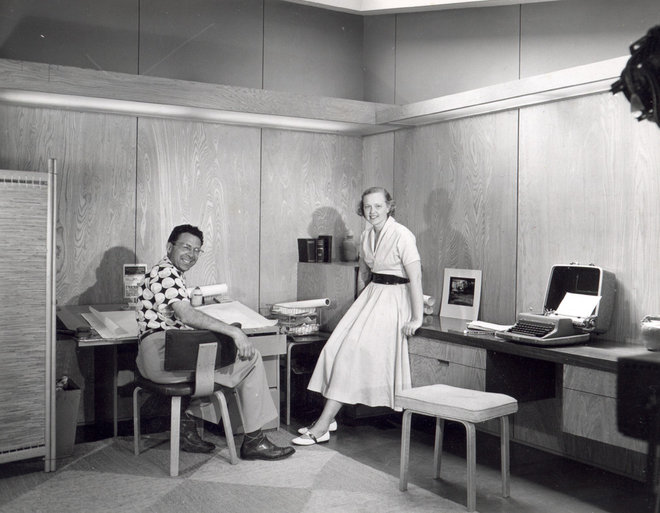

In the late 1950s, Gray’s father, David Harvey, a physician in nearby Ventura, and her mother, Jeanne, an active player in county and state politics, met Rodney Walker and his wife, Dorothea, through a local recorder group that got together to practice playing the woodwind instrument.

After Gray’s father expressed dismay at trying to find someone to design a new home within his budget, Walker, who’d developed building principles rooted in affordability and efficiency since his Case Study House days, agreed to take on the project. “This house was designed to be affordable,” Gray says. “My parents weren’t rich people. You just have to find architects who are creative.”

But when Gray returned to her childhood home last year, she found it wasn’t as well-preserved as her memories of the lively cocktail parties her parents once threw there.She hired Allen Construction to spearhead the modest update while preserving the rest of the design, including the old-growth-redwood framing.

Many of the large, single-pane windows are original, though a few shattered when Gray was growing up during flight testing at a nearby Air Force base, she says. Sometimes when a plane broke the sound barrier, the reverberation would break a window. “It happened more than once,” Gray says. “My mother would call the base and someone would come out and replace the window for us.”

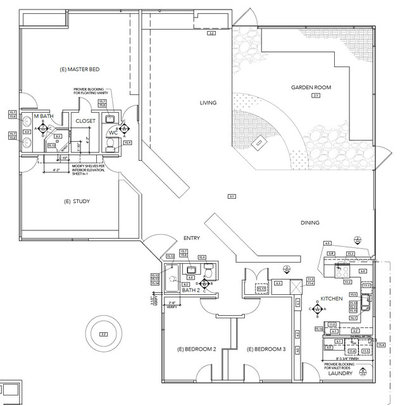

Apart from the kitchen and bathrooms, Gray left the home as close to original as she could. She didn’t remove any walls or add any square footage. The layout is virtually the same as the day she moved in as a little girl. “The original design is perfect,” she says.

The acid-stained concrete floors are original, except where Gray replaced a few chipped corners. “After 50 years, it has a patina,” she says. “To me, it’s handsome.”

The wood-burning fireplace is also original and “puts out a huge amount of heat,” Gray says. An original interior garden, another Walker hallmark, sits near a wall of windows.

She also keeps fish in the pond, just like her parents did. “The pond hadn’t been resealed since the 1950s, so it leaked and moisture leached underneath the concrete floor and caused damage,” she says. She repaired the floors and added a water barrier to the pond.

In all her years growing up, Gray says, two people fell into the pond. “One was a kid with a glass of chocolate milk, the other was a cocktail-party-goer.”

BEFORE: Gray’s mother, Jeanne, is seen here in 1966. After its completion in 1959, the home saw frequent visitors.

“It was the 1950s, the heyday of the cocktail party, and my parents entertained a great deal,” Gray says. “This is a wonderful party house. It’s very open. Grownups would come in their cocktail dresses and high-heel shoes and suits and eat nuts and olives and drink cocktails and then careen home.”

Many of the light fixtures are original, though Gray replaced the bulbs with LEDs.

The leather Hardoy butterfly chair at the right is from the 1950s. “They are fantastic,” Gray says. “You can’t buy covers anymore that fit. The new ones are different sizes.”

In front of the fireplace, two Hans Wegner saddleback chairs sit by a slate-and-glass coffee table that Gray’s father designed. The sofa is a Danish modern piece that her mother found abandoned on the side of the road in the 1960s. Her father also designed the teak and stainless steel dining table in the foreground. There are some Eames plywood chairs elsewhere in the home.

A barrier originally separated the kitchen from the living and dining area, and stuck out in a way that partially blocked the handle to the sliding glass door. Gray pushed things back 6 inches to line up the peninsula flush with the door. And since new appliances require deeper space than those of the 1950s, she encroached into a laundry and utility room behind the refrigerator. She also ran propane to replace some of the electric appliances.

A mosaic tile backsplash also adds a burst of color. The cabinets are sapele wood, which is in the mahogany family. A wall of cabinetry on the right extends down a narrow hallway to become display space for Gray’s ceramics collection.

Counters: Red Glitter, Qortstone

The horizontal window over the mirror is original, as is the light fixture. The counter is purple quartz with bits of green glass. Gray removed asbestos tile on the floor to reveal the concrete, which she repaired to be consistent with the rest of the home.

Light fixture: Element Twenty light island (206-520), Corbett Lighting; tile: Murano Vena, Hirsch Glass

Light fixture: Ring shade (22 inches), LED pendant, Sonneman; tile: Vibe white moasic, Walker Zanger

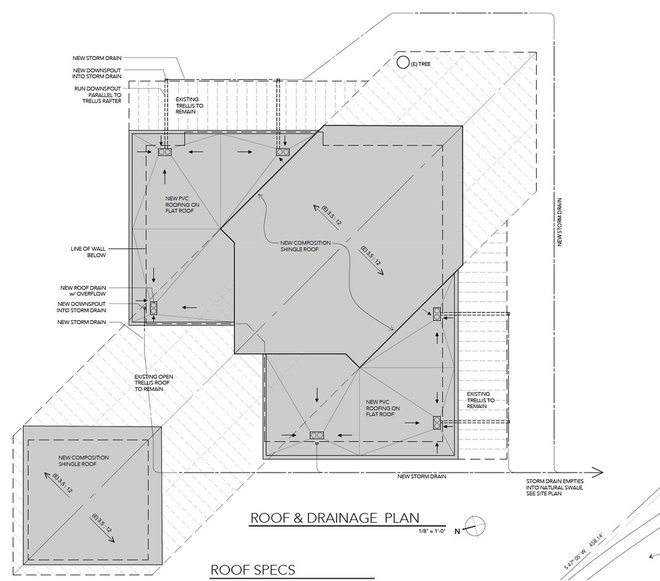

When the home was built, Walker had just finished designing and building his own home nearby, and he used some of his experimentations on that home in designing the Grays’ house, particularly evident in his roof design.

Previously, Walker’s roofs were hot mop and gravel constructions, but “he started changing things in Ojai,” says Craig Walker, Rodney’s son. “He began using a lot more glass and steel.”

Matt Caligiure of Allen Construction came on board as the project manager to tackle the leaky roof. He discovered the problem had to do with the innovative I-beam structure of the home. A pitched roof covers the large living room, while the roof over the surrounding bedrooms is flat. Leakage mostly occurred in the areas where the flat portion met the beams. “The biggest obstacle was figuring out how to shed water instead of it becoming a swimming pool up there,” Caligiure says.

He and and general foreman Evan Warren took everything off and started from scratch. An entirely new roof now envelops the beams and prevents leakage, while presloped panels encourage water to stream toward four new drains.

“We encased everything from the top,” Caligiure says. “It’s bulletproof now. It feels good to solve a 50-year-old problem and move on. As soon as the first rain came, I drove 45 minutes out to the home, threw up a ladder and stood on the flat roof and watched all the water go where I wanted it to go, into the drains we designed, out the downspout and away from the house. That felt good.”

Today, people ask Gray if she’s concerned about earthquakes and energy costs, but she dismisses both. “It’s a steel-frame house,” she says. “It’s experienced earthquakes here for the last 60 years and nothing has ever happened to the structure.

“Energy-wise,” she says, “the house was built when energy was cheap. They didn’t think about it at all. For me, the total annual expenditure is no more than it is to live in the East, where it snows.” Plus, the new UV blockers help mitigate some heat gain.

Caligiure had never heard of Rodney Walker before getting involved with this project. Now he’s working on two other Walker structures in the area, including the designer’s home. “Two years ago I’d never heard of him,” Caligiure says. “Now I’ve got three of his projects under my belt. Interesting how things work.”

The Era Lives On

After designing and building seven homes in Ojai, Walker lost interest in building houses, says Craig, a retired teacher. In 1964, Walker got out of the business altogether and went on to do other things, such as running a local hotel and owning a store where he made and sold jewelry. He also worked an entire year on designing an automatic pool cleaner, “but someone beat him to it,” Craig says.

Walker’s Case Study Houses remain popular in Los Angeles, although not many still look like the original designs. Craig says he can think of a dozen that are in fairly pristine shape. Zac Efron recently lived in Walker’s Case Study House No. 17, but by that point it was unrecognizable from the original, Craig says.

“He was very inventive and always liked to solve problems in his work,” Craig says of his father. “He was always trying different things, so it’s possible here and there that in the long term some didn’t work out. But I’m surprised that when you look at his homes that do exist today what great shape they’re in.”